Written by Laureen Bokanda-Masson

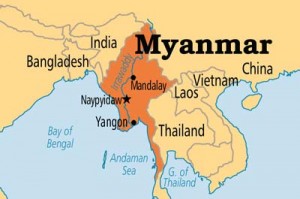

Following the attack of border-control posts carried out by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) on 25 August 2017, the Burmese military has responded by conducting repression operations leading to a new major wave of migration in an attempt by the Rohingya to flee inter-community violence. Though the tensions are largely construed as religious and ethnic, it is contended that the persecution of the minority is also economically driven.

On the ground of the 1982 Citizenship law, the Rohingya were collectively stripped of their Burmese nationality and rendered stateless, resulting in significant social impediments, economic constraint and deprivation of fundamental rights. Their lack of status bleeds into all aspects of their life as the Rohingya face several restrictions on their right to free movement, right to vote, right to property, access to education, employment and health, whilst also being submitted to marriage and population control measures. These marginalising policies also exclude the Rohingya from the distribution of resources and perpetuate the widespread practice of land grabbing in Myanmar. In this regard, NGOs and the UNHCR have been reporting violations of international criminal and human rights standards, such as extrajudicial killings (including shooting civilians), pillage, forced labour, rape and sexual violence, pogroms, religious persecution, forced sterilisation, and arbitrary detention in retention camps.

Understanding the dynamics of ethnic relations in Rakhine State, and by extension in Myanmar, is central to comprehending the roots of the crisis. The prevailing climate of hatred and persecution is fuelled by extreme nationalist Buddhists claiming that the Rohingya are Chittagongian people, a Bengalese community which arrived in Myanmar with the British settlers. Within this rhetoric, the presence of the Rohingya on Burmese soil represents a threat to the Buddhist identity, a gateway to Myanmar’s ‘islamisation’, but also, and less mentioned, additional competition for local resources.

After 50 years of strict military rule, the emergence of Myanmar from its diplomatic and economic isolation entails the rise of salient territorial and economic implications to the ethnic conflict. As China, the US – two permanent members of the UN Security Council – and India are competing for influence in Myanmar, the poverty-stricken region is also struggling not to be looted of its natural resources by the military, conglomerates close to the military or by private corporations. In fact, in addition to Myanmar’s gas and oil supplies, Rakhine State’s natural resources, such as timber, jade and other precious stones, as well as its hydraulic potential are crucial interests.

While most of the legal debate focuses on the categorisation of the ethnic conflict, to determine whether it falls within the meaning of genocide or ethnic cleansing,[1] it is interesting to note that the multi-faceted issue aligns with the burgeoning concern with economic aspects of conflicts in international criminal law. The question that naturally arises from such consideration is the extent to which international criminal law can and/or should address the economic dimensions of systemic persecution, gross violations of human rights or mass atrocities.

Regardless of the motive, and whether the conflict is religiously, politically and/or economically driven, allegations of mass torture, mass rape, and mass murder carried out by or on behalf of the military could be addressed through international criminal legal mechanisms. Myanmar is not a signatory party to the Rome Statute. However, the UN Security Council, which has met twice since the outbreak of violence and issued a rare rebuke, could refer the case to the International Criminal Court’s Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) to investigate allegations of crimes against humanity, gross violations of human rights, and potentially genocide.

Motive should not be deemed irrelevant or remote. Although international criminal law focuses on intent to determine culpability, understanding and taking into account motive also allows a fuller understanding of the conflict and is vital in terms of transitional justice. While not necessary to prove liability, motive remains a key component to building a strong narrative. Motive could also be considered for sentencing and categorisation of a crime. For instance, traditionally defined crimes of persecution or pillage would fail adequately to capture the act of systemic persecution of a determined group in correlation with natural resources exploitation.

Considering all dimensions of the Rohingya issue appears as a prerequisite to fully grasp and tackle the marginalisation of the minority though institutionalised policies, as well as the absence of accountability or efficiently deterrent measures. As mining, timber, and geothermal projects are developing in Myanmar, international criminal law may be pushed to fully integrate into its rationale the role of economic motive and resource exploitation in fuelling conflicts. Failing to do so may very well prevent international criminal law from adopting a tailored approach to modern conflicts. If the Rohingya crisis may not be the case that will spark a shift in practice, it certainly supports the increasing awareness of the role of economic interests and actors in conflicts and the current demand that international criminal law evolve to address business dimensions of conflicts.

Meanwhile, though the plight of the persecuted minority has stirred deep emotion, particularly in the Muslims world, the international community has yet to take efficient steps to resolve or prevent further escalation in the unfolding humanitarian crisis in Myanmar. There is heightened concern stemming from the involvement of Islamist groups calling for jihad volunteers or vowing to launch attacks.[2] This has raised the spectre of targeted attacks on Myanmar soil, but also radicalisation of the Rohingya and intervention of foreign Islamist fighters in the volatile region. The exploitation of the tensions and violence in Rakhine, following ISIS setbacks in Iraq and Syria, would represent an opportunity of expansion beyond the Middle East for the terrorist organisation. It would create a second front in South East Asia, as the Filipino forces have been combatting the ISIS-affiliated terrorist group Maute since May, and as jihadism has been rising in Bangladesh in the past few years. The advisory commission on Rakhine State led by Kofi Annan indicated in its final report, submitted on 23 August 2017:

If human rights concerns are nor properly addressed – and if the population remain politically and economically marginalized – northern Rakhine State may provide fertile ground for radicalization, as local communities may become increasingly vulnerable to recruitment by extremists. If not addressed properly, this may not only undermine prospects for development and inter-communal cohesion, but also the overall security of the state.[3]

[1] UN officials and several NGO have been referring to an on-going ‘ethnic cleansing’, which is not a recognised independent crime under international law; hence, denying the categorisation of the systemic persecution as genocide. It is contented by some, that the violence and coercive practices do not amount to genocide, considering the absence of physical destruction or extermination and intent thereof.

[2] The ISIS Chief, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, has mentioned their ‘brothers’ in Myanmar, while the Al-Qaeda leader in Yemen called to carry out attacks in Myanmar and the ISIS offshoot in Bangladesh has vowed to launch attacks when in capacity to do so. Finally, the Indonesian Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) has called for volunteers to wage jihad in defense of the Rohingya.

[3] Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, Towards a peaceful, fair and prosperous future for the people of Rakine, Final report of the advisory Commission on Rakhine State, August 2017, p15, Available at [http://www.rakhinecommission.org/app/uploads/2017/08/FinalReport_Eng.pdf].

Image source: rstv.nic.in