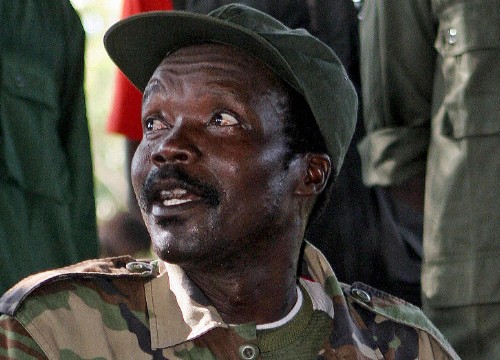

Joseph Kony is the self-proclaimed messianic leader of the ‘Lord’s Resistance Army’ (LRA) who have, under his authority, spent nearly thirty years engaged in a brutal campaign to overthrow Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni. The rebel group is responsible for butchering 100,000 innocent civilians and abducting up to 30,000 children who are forced to become soldiers, domestic help or sex slaves in order to replenish the militia’s ranks.

In response to international pressure to clamp down on Kony, Museveni referred the situation in northern Uganda to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in December 2003. By July 2005 the arrest warrants for five senior LRA commanders were announced; Kony faced 12 counts for crimes against humanity and 21 counts for war crimes including sexual enslavement and forced enlistment of children.

The ICC’s leverage in extraditing Kony is extremely limited in that it is an international court and lacks independent enforcement. It is therefore crucial for the government of Uganda and other international bodies to comply with the ICC’s warrant. Former ICC Chief Prosecutor, Luis Moreno Campo, asserted: “we expect them [Uganda] to execute their legal duties.” However, all operations searching for Kony came to a grinding halt in August 2006 when peace negotiations began in Juba, South Sudan.

For over two years, mediators from the Government of Southern Sudan worked tirelessly with LRA spokesmen to negotiate an agreement that would put an end to the ruthless attacks. However, the ceasefire agreed between LRA commander Vincent Otti and the Ugandan government, came to an end in late 2008 when Kony refused to sign the agreement.

A further obstacle to enforcing the warrant has been the LRA’s dispersal into Uganda’s neighbouring countries: South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the Central African Republic (CAR). As of 2010, the militia group has operated in small bands of just 15-20. Hidden, often beneath the thick dense canopy of the CAR jungle, the rebels remain concealed from military aircrafts to this day. The LRA are becoming increasingly elusive and isolated. Long ago abandoning mobile phones, the militia cannot be tracked by satellite technology. Tom Ogola, a senior member of the rebel group who defected in 2014, has stated “I have not seen or communicated with our leader since 2008.”

Political tensions continue to obstruct the search for Kony. In April 2013, search efforts were forcibly ended when the Muslim rebel group ‘Seleka’ seized power in the CAR, refusing to co-operate with the 5,000 African Union and 300 U.S. Special Operations troops searching for Kony. Until September 2014, unmonitored violence ensued in an essentially lawless CAR, providing the perfect environment for Kony and his rebels to hide. A further eminent threat is the increasingly unstable bilateral relations between Uganda and the U.S government. Homosexuality in Uganda has been prohibited since the 1950s, however, the country’s new anti-gay bill has faced widespread criticism for requiring citizens to report homosexuals to the police. As a result of the public outcry, Obama has been under growing pressure to withdraw all U.S. troops searching for Kony.

What will happen if Kony is caught?

On the one hand, Kony could face prosecution in Uganda. Such a solution would appear to align with the Court’s complementarity principle, which holds that the ICC should seek to complement domestic proceedings. Prosecution in a domestic context would satisfy the Court’s desire to “put an end to impunity”, while allowing the ICC to preserve some of its limited resources for future prosecutions. Uganda would, in theory, be able to re-claim Kony’s case by challenging its admissibility under Article 17 of the Rome Statute, on the grounds that they are able and willing to prosecute him. Under Ugandan jurisdiction Kony could face capital punishment, in lieu of receiving a maximum sentence of life imprisonment from the ICC.

On the other hand, allowing the Ugandan government to prosecute Kony may create an unsettling perception that the ICC is merely a political tool, as opposed to a vehicle for dispensing justice. This is troubling as it could prompt other countries to flippantly self-refer cases to the Court, only to withdraw them once the ICC has done the majority of the legwork.

If the ICC refused an admissibility challenge from the Ugandan government, it risks being accused of going beyond their powers laid out in the Rome Statute and intruding on state sovereignty. In such a scenario the ICC have three possible responses. Firstly, it could be argued that the Ugandan government waived their right to challenge admissibility when they self-referred the case to the ICC. Secondly, the admissibility challenge would be over a decade after the arrest warrant was issued, and therefore not “at the earliest opportunity”, as stipulated in Article 19(5) of the Rome Statute. Finally, under Article 17 of the Statute, the domestic proceedings must be “independent and impartial”, which could be a point of contention given Museveni’s personal 30 year-long vendetta against Kony.

In conclusion, Kony’s search remains perilously close to collapsing. The increasingly reluctant U.S. government, combined with recent reports of Kony’s ill health, suggest the warlord may never be brought to justice. However, in the event of his capture, the ICC must think carefully about whether to accept an admissibility challenge to Kony’s prosecution. The decision the ICC makes will establish an important precedent for all future self-referrals, and therefore have significant implications for the future perception of the Court.

Image source: edition.cnn.com

Text by: Serena Crawshay-Williams